Challenging U.S. leadership, Chinese industry, academia, and consumers are making artificial intelligence a way of life.

Inside one of this city’s busiest subway stations, throngs of commuters walk down a long passageway as they transfer between subway lines. The walls and columns are plastered over completely with bright green pop-art-inspired billboard advertisements, impossible to ignore. “Wow!” a white-collar worker exclaims in one ad, gushing about the virtual tutor on a language-learning platform powered by artificial intelligence. “My AI teacher caters so well to my needs, I’m obsessed with learning English now.” The marketing campaign by the start-up Liulishuo seems to be working. Introduced in July 2016, the company’s “AI English teacher” app boasted almost 600,000 paying users a year later. It’s one example of how mainstream AI has become in China. Another comes from a computer scientist, speaking at a recent academic forum here: Even taxi drivers, he says, want to discuss deep learning and AI with him.

From major tech and Internet companies to start-ups, airports, local police, hospitals, and individual consumers, Chinese are rapidly developing and using what Google, which itself has a big stake in AI, defines as “the theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, and translation between languages.” Given China’s growing investment in research and AI-oriented start-ups, including some in the United States, this expansion should only continue. In July, China’s top-level State Council put its official stamp on the trend, declaring that by 2030, the country will become a leading (one translation said “world’s premier”) artificial intelligence innovation center. “We must take the initiative to firmly grasp the next stage of AI development to create a new competitive advantage, open the development of new industries, and improve the protection of national security,” the council said.

Liulishuo (that’s Mandarin for “speak fluently”) draws on a combination of speech recognition, machine learning, and big data—along with gaming, social media, and neuroscience—to create a personalized learning experience: the customer-friendly “AI English teacher.” Founded in 2012, the firm is led by CEO Wang Yi, a Princeton computer science graduate who spent two years as a Google product manager before he and his co-founders seized the chance to return to China and build a company using AI technology. An obvious niche was the high demand among ambitious Chinese for English-language skills. Wang thought he could improve on the English-language training schools doing a brisk business in China. As Bloomberg has reported, Liulishuo “built algorithms that quantify dozens of dimensions of speech,” such as pronunciation, grammar, and fluency. Rather than requiring memorization, the formulas are designed to activate subconscious pattern recognition. Entertaining app users as they learn, Liulishuo includes a feature that lets them dub their voices over movies and TV shows. Launched in 2012, Liulishuo’s free version has drawn over 45 million users. The company brags it can teach English in a third of the time it would take with a human teacher in a training center. In turn, data from these users let the firm generate what it claims is the world’s largest speech bank of Chinese people speaking English and refine its methods of adapting to individual learners.

Surf that Wave

At 39, Wang is the elder statesman of his company, but he looks as youthful as his millennial colleagues busily working on a mobile English learning platform at the company’s Shanghai headquarters. With summer temperatures outside soaring above 100 degrees, he’s dressed casually in black geek-chic glasses, shorts, and a gray T-shirt that reads, “I love it when you call me Big Data.” Chinese entrepreneurs, says Wang, “know that they have a big opportunity in front of them, and they are trying their best to capture that. The wave is half-formed and for any good surfer, you just want to surf that wave.”

China aims to be the crest of the wave. While some say Beijing came late to the AI game, it wasn’t standing still before July’s policy announcement, which set a target of $59 billion in output by 2025 focusing on AI software and hardware, intelligent robotics and vehicles, virtual reality, and augmented reality R&D. In February, Chinese Internet giant Baidu announced it had received funding from China’s National Development and Reform Commission to lead the creation of a national deep learning lab. In March, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang mentioned AI for the first time in his annual Work Report as part of the National People’s Congress, thereby flagging AI as a priority.

A Go tournament in May in the city of Wuzhen became “a sort of Sputnik moment” for Beijing, spurring July’s announcement, the New York Times reported. AlphaGo, a machine built at the Google-owned DeepMind artificial intelligence lab, beat Chinese grandmaster Ke Jie, the world Go champion, in a three-game match. China’s government blocked live coverage, but the tournament nonetheless made an impact. Wang recalls: “By creating the drama of human Go champions playing with AI, it really caught people’s attention, and it demonstrated, although arguably in a very restricted setting, [AI] is good enough.” China may in fact not have been far behind Google in the AI-Go sweepstakes. In March, Fine Art, a program created by the Chinese company Tencent, won the 10th Computer Go UEC Cup championship, competing against 30 of the world’s best AI Go programs, such as Facebook’s Darkforest.

Well before the State Council announcement, Chinese academics were deep into AI, churning out papers in the discipline at twice the rate of their U.S. counterparts between 2010 and 2015 (although they ranked only 34th in terms of citation impact). In the same time period, the number of AI patent submissions coming from China jumped 190 percent while U.S. patent submissions rose 26 percent (but to a total of more than 15,000, much more than China’s 8,410). “Chinese research in AI has grown exponentially, unseating the early leader, the United States,” concludes the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, created by Congress. Meanwhile, Chinese companies are “ringing alarm bells” in Washington by investing in cutting-edge U.S. start-ups, the New York Times reports. Citing an unpublished Pentagon-commissioned white paper, the newspaper says: “Beijing is encouraging Chinese companies with close government ties to invest in American start-ups specializing in critical technologies like artificial intelligence and robots to advance China’s military capacity as well as its economy.”

Before Boarding, a Face Scan

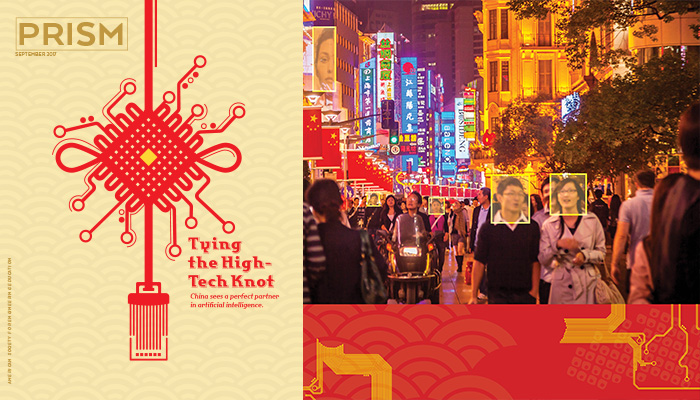

So far, industry has been the most visible driver of the AI revolution in China, particularly with facial-recognition technology. Some airports and tourist sites have already put face recognition to use for admission and check-in and boarding. The South China Morning Post reports that China Southern Airlines began allowing passengers at an airport in Henan Province to have their faces scanned in lieu of using boarding passes. Alibaba announced earlier this year that face recognition technology may be incorporated for mobile payments. Increasingly, local authorities are using AI to control behavior. Shanghai’s police recently announced they are the latest of several cities’ police departments to roll out face-recognition technology to catch and shame jaywalkers. Chinese companies are developing technology that they claim can identify and catch suspects before they even commit a crime. And last year, Beijing-headquartered Baidu, one of the world’s biggest Internet companies, made its cross-age face recognition technology available to a nongovernmental organization helping families find trafficked children. The technology, also known as age-variant face recognition, distinguishes between facial features that change with age and those that remain intact to identify people based on images captured when they were younger. So far it has been successful in reuniting several families, including a family whose son was abducted 27 years ago. Voice-recognition software is also spreading. In July, Alibaba launched Tmall Genie, a digital assistant speaker similar to Amazon’s Echo, which performs tasks and delivers information in response to voice commands.

Baidu’s autonomous car project is attracting a lot of attention for the potential applications it could have in public transport. Baidu CEO Robin Li thinks that a driverless car will be on the road in China by 2020. That’s assuming China’s legal framework catches up. After he demonstrated Baidu’s autonomous car through livestreaming at a Baidu Developer Conference earlier this year, Beijing’s traffic police rebuked him for breaking a law requiring drivers to keep their hands on the steering wheel.

AI advances are also being applied in health care. Some Chinese hospitals use AI to read CT scans. Start-ups are using AI to help patients keep track of and manage their personal health. Last year Baidu unveiled a chat bot for patients and doctors to communicate. This spring a start-up unveiled an AI computer vision tool to diagnose lung cancer. Another new firm, A-Tag Technology, is investigating the use of face-recognition technology to identify skin diseases and rashes.

Big Market = Big Data

Academics and entrepreneurs cite several reasons to be bullish on China’s future as an AI superpower. China’s massive population, which can be seen as a disadvantage in urban livability, provides not only a vast potential market for AI technology but a source of data for such applications as voice and face recognition. “Big market can also be understood as big data. China has so many people, so that means China has so much data. That means AI systems can be trained very well and work very well,” says A-Tag Technology cofounder Zhang Haoxi, an associate professor at Chengdu University of Information Technology who works on machine learning and the Internet of Things.

“If you have a small market, you don’t necessarily need to use AI. When you reach a certain level of scale data set, then AI becomes really meaningful,” says Wang. While Chinese research collaboration with academics in the United States and elsewhere has grown in recent years, the amount of data available in China adds to the international appeal, says Feng Jian Feng, a professor of brain science at Fudan University’s Institute of Science and Technology for Brain-Inspired Intelligence. “It’s really for mutual benefit.”

A June report published by Washington’s Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars noted that cutting-edge AI technologies are often deployed faster in China than in the U.S., due to high customer loyalty and speedy integration of AI into existing products. Baidu’s online translation system, for instance, used neural networks a year before Google’s neural machine translation caught industry attention.

Another benefit to AI technology researchers and developers stems from the country’s tight security apparatus, which has accustomed the population to more government intrusion in their lives than most democracies would allow. As a result, privacy protections are weaker than in the West, and Chinese society in general is used to private data being captured without an individual’s permission. “In the U.S., it is not easy to acquire so much data. In this way, we have an advantage,” says Gao Shenghua, an assistant professor of computer vision at ShanghaiTech University. Zhang Haoxi adds, “In the U.S. the rules are very settled. You cannot break the laws or rules, and sometimes this can be a disadvantage to trying new things.” In China, he says, “We have a very flexible environment for trying new ideas. Sometimes there are no clear rules for something. Then it becomes an advantage for start-ups to do business. It gives them windows to try new ideas.”

‘Not a Top Research Country’

If entrepreneurs feel less restrained, the same can’t necessarily be said of academic researchers, whom China needs to pursue the discoveries that form the fundamental building blocks for innovation. Low pay, lack of a tenure track, and a backward system of research funding loom as potential impediments to China’s drive to become preeminent in AI. Dawn Song, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California-Berkeley, contends that China still lacks an environment where researchers can thrive. “China is not a top research country yet,” Song, a 2010 MacArthur Fellow, told a recent forum in Shanghai entitled Securing the Future with AI. “We need to have a good ecosystem. If you want to attract the best people, you have to create the best environment and retain the best talents.” She added, “For now, they export the best students to all go study abroad.”

Li Kai, professor of computer science at Princeton, who spoke at the same forum, agrees. “There has to be a culture to support you to do whatever is important,” he says. Having earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in China and then a Ph.D. from Yale, he is familiar with both U.S. and Chinese systems and says the research environment here is not yet one that allows academics to freely pursue their interests. “It can’t be too linked to funding and government-led initiatives. I know many professors in China agree with me. The scientists are not brave enough or capable enough to work on what is most important to them. They still have to find the funds for their research.”

Many students eventually return to China, but when they do, there’s a good chance they’ll be lured away from academia by industry, which can pay three to five times as much. “The market demand for AI talents has been surging in recent years, so there’s a shortage at this time,” says Liulishuo’s Wang Yi. “I think in China, because there’s a huge supply of venture money and a shortage of AI talents, this may be more pronounced.” Government funding doesn’t match its aspirations, some academics say. The grant system, while getting stronger, “is less forward looking and less flexible” than is needed, says Zhang Zheng, professor of computer science at NYU Shanghai. “The grant money is not up to the U.S. standard. The hot money is all in the VC [world]. Why not divert some of that to basic research that doesn’t [yet] exist?”

China also lags in partnerships between Chinese industry and universities, some academics say. Zhang Haoxi wants Chinese universities to forge more relationships with companies of the kind that allows Yann LeCun, Facebook’s AI Research director, to retain a part-time professorship at New York University: “This could be a very good thing both for universities and industry development for applications.” Some schools are headed in this direction. One is ShanghaiTech University, which opened in 2013 in Shanghai’s Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Zone, surrounded by R&D facilities, and has adopted a tenure track. Gao Shenghua, an object-and-face recognition expert who joined the university after a postdoc in Singapore, says the school encourages industry cooperation. His department, the School of Information Science and Technology, is collaborating with United Imaging, a nearby company offering medical solutions using computer imaging.

Research Vs. “Quick Money”

“How we can get businesses to be involved in long-time research? This is a big problem,” says NYU Shanghai’s Zhang Zheng. He added, “There is no long-range research yet in the VC community here. They are near-sighted.” Zhang Haoxi added, “To have our own companies which are willing to invest in real research rather than making quick money, this is basically the main challenge for China.” He said that to some extent Alibaba and Baidu are doing this, but not enough. “There is still a long way to go for them.”

Sufficient capital isn’t a problem, says Wang Yi. “Some of the AI companies in China have even higher valuations than U.S. companies these days. People are saying there’s no shortage of venture capital; there’s just shortage of good companies to invest in.” But Zhang Zheng says investments are narrowly focused. “In China we have a lot of hot money focused in one or two areas, spent in a limited area.”

Whatever gaps exist now in China’s investment strategy, the country has a track record of rapidly catching on and catching up. Can cutthroat U.S.-China competition be avoided? Alibaba chairman Jack Ma sought to play down that prospect at a recent World Intelligence Congress in Tianjin, saying, “We need to put more time [into] thinking about the future, not about how to fight our competitors. We need to work together with the U.S. to solve challenges. We have already passed the era of competing.” The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission has a different take: “Competition between U.S. and Chinese firms is only set to increase as the Chinese government is throwing its support behind its commercial and military AI researchers.” Not long ago, Chinese entrepreneurs were infamous for snatching and exploiting U.S.-grown technology. That’s changing. “The U.S. entrepreneurs are now watching more closely what’s happening in China and wanting to copy or get inspired by what’s happening here,” says Yi. If he’s right, U.S. billboards could soon show delighted American students praising their “AI Chinese teacher.”

By Rebecca Kanthor

Rebecca Kanthor is a Shanghai-based writer and a correspondent for Plastics News. She works part-time as a proofreader for ShanghaiTech University, one of the institutions mentioned in this article.

Design by Nicola Nittoli